The National Transportation Safety Board on Tuesday February 7 said that the El Faro, a cargo ship which sank in the Atlantic Ocean on October 1 2015, sank due to inaction by the captain, an outdated weather briefing, and lack of safety oversight provided by the captain’s employer. The ship sank 40 miles northeast of the Bahamas, killing all 33 people onboard.

The NTSB found that 11 issues contributed to the ship’s sinking and issued recommendations to seven companies and agencies for what each group needs to address.

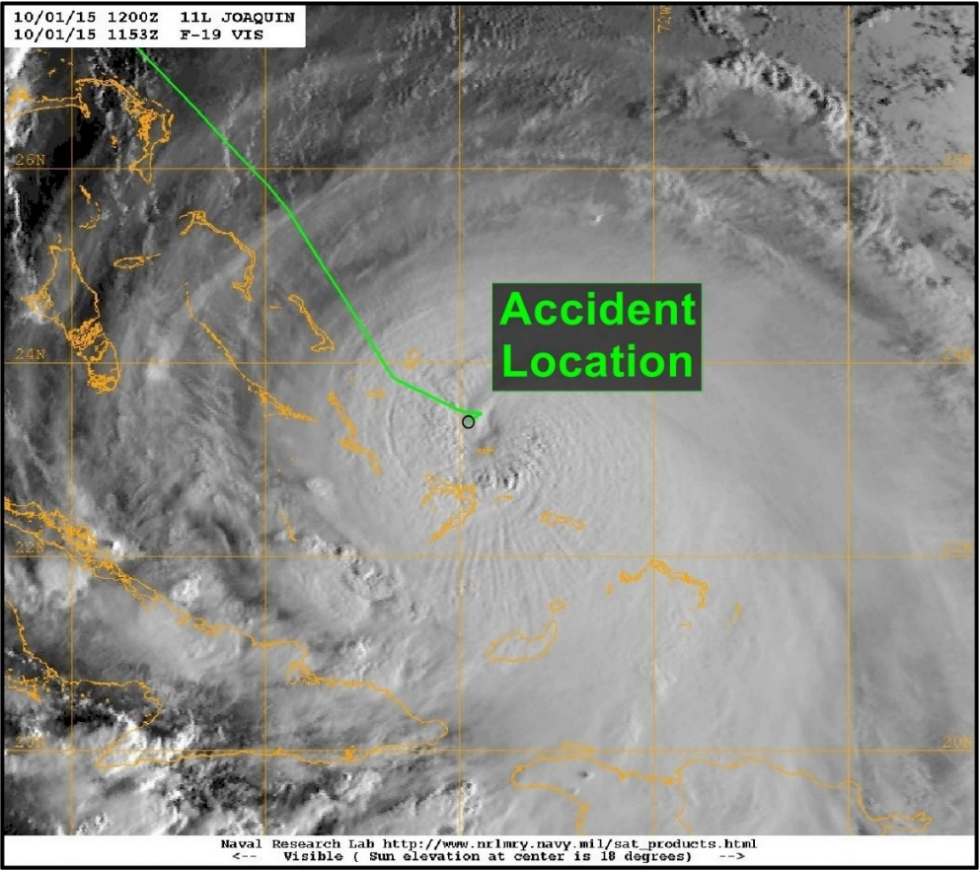

At the time of its trip, the SS El Faro was a 40-year-old ship owned by TOTE Maritime Puerto Rico operated by TOTE Services, Inc. traveling from Jacksonville, Florida to San Juan, Puerto Rico. The ship’s route placed it directly in the path of Hurricane Joaquin, at the time a Category 3 storm which strengthened to Category 4 approximately 20 minutes after the ship sank.

The NTSB and the U.S. Navy began attempting to locate the El Faro and recover it’s Voyage Data Recorder four days after its sinking. The search for the ship ended November 15 after they couldn’t locate the VDR. A second search for the vessel was conducted in April 2016 when the National Science Foundation and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution began searching and successfully discovered the VDR on April 26. It was recovered on August 12 and then transported to NTSB headquarters in D.C. for analysis.

Some weather information distributed, but not enough

According to the report, an off duty second mate on the El Faro notified the captain on September 29 of a storm forming north of the Bahamas – which would turn into Hurricane Joaquin the next day – but the captain made no effort to change the ship’s course, but replied that they would “steam our normal direct route” to San Juan. The captain believed that the storm would remain north of their normal route.

The NTSB was able to recover audio from the ship’s bridge back to September 30, which was used to inform their analysis. The ship’s data recorders also saved captured radar images, information about the ship’s heading, wind speed and direction. The national Hurricane Center had upgraded the hurricane watch to a hurricane warning earlier in the day, meaning that a hurricane would be expected to form within 36 hours. The captain received an email with updated weather information one and a half hours later that morning, which was consistent with the NHC’s forecast.

At 6:55 a.m. on the 30th the captain asked his chief mate if he was comfortable with a recent course change to stay away from the hurricane, which he was, while noting that the other option they had was “drastic.” The captain and chief mate informed some other crew of “heavy weather tonight” and the captain left the bridge at 7:25 a.m. to verify that the ship’s containers were tied down properly.

The ship’s crew continued to discuss weather including Tropical Storm Erika which the ship diverted further south than usual for as the morning progressed. The report notes “the captain said that Erika was the first real storm he had ever been in with El Faro and that the ship was ‘solid’.” The captain and third mate continued noting the ship is “solid it’s just all…the associated bits and pieces…the hull itself is fine – the plant no problem.” The two saw no issues with the ship holding up during the expected severe weather.

“We’re gonna make it, we’re gonna make it.”

-Statement by either El Faro’s captain or third mate

Emails obtained by the NTSB between El Faro’s captain and another ship around 330 miles southeast, the El Yunque, show the captain believed their ship would “ducker underneath” the hurricane and that they would be fine, even though the El Yunque’s captain emailed and remarked the storm was “steadily intensifying and tracking to the SW.”

“We are heading straight into a hurricane.”

-El Faro’s second mate to her mother

El Faro’s captain received another updated weather email at 11:03 a.m. also on the 30th, but additional information did not cause him to drastically change the ship’s course. “These ships can take it,” he told the second mate.

The ship’s VDR recorded at least two Coast Guard aircraft sécurité messages notifying that a hurricane warning had been issued for the Bahamas and requested “extreme caution” from mariners later on the 30th. The crew continued discussing worsening conditions through the day, noting even that “We are going to go right through the [expletive] eye.” At 6:08 p.m. that day, the Ocean Prediction Center broadcast a notice warning of waves between 12 and 27 feet within the storm’s center, and predicted maximum 30-foot waves for noon on October 1.

At 1:41 a.m. the second mate reported after a phone call with the captain that he had been sound asleep; the hurricane had become a Category 3 half an hour earlier. An off-course alarm began sounding first at 3:00 a.m. when the ship was on autopilot, and then again at 3:20 a.m., indicating the strength of the waves and wind pushing the ship around.

The captain arrived on the bridge at 4:09 a.m. The El Faro’s Sat-C satellite terminal received a National Hurricane Center advisory half an hour later noting the storm had sustained 105 knot winds with gusts up to 130 knots, moving west-southwest. The ship was approximately 11 miles northwest of the storm.

Flooding was reported around 5:45 a.m. on October 1 in the 3rd hold in the ship and the crew began attempting to pump the water out. Ballast water was transferred around the ship to attempt to keep it level. The ship lost its power generation plant just after 6 in the morning, and the ship’s speed dropped to 0.5 knots.

The captain called TOTE’s emergency call center at 7:01 a.m. to notify the company of a hull breach, and that the ship was continuing to take on water and was leaning. The ship’s propulsion system was still inoperable. A distress signal was sent at 7:13 a.m. by the second mate, and at 7:15 a.m. the distress call was forwarded to the Coast Guard’s rescue coordination center in Portsmouth, Virginia. A second notification was sent at 7:17 a.m. to TOTE. “We’re gonna be good,” the captain remarked. “We’re gonna make it right here.”

A call to abandon ship was made at 7:29 a.m. by the captain, and the forward portion of the ship appears to have gone underwater a minute later. The VDR audio recordings ended at 7:39 a.m. No further communications from the El Faro were received by either the Coast Guard or TOTE. Hurricane Joaquin at that time had maximum sustained winds of 104 knots, and hurricane-force winds extended up to 30 miles out of the storm’s center.

The last known position of the El Faro was 17 miles from the hurricane’s center, reported 20 minutes before sinking.

No weather information provided by TOTE

The NTSB found that TOTE did not issue any safety alerts for Tropical Storm Erika earlier in the season, nor Hurricane Joaquin before or during the accident voyage. Nine other companies surveyed by the NTSB that operated on similar routes said that all provided weather-routing services to their vessel masters, and that eight held weather-related discussions with the vessel masters.

The only discussion between TOTE and the El Faro’s captain which the NTSB found was by email; the only telephone contact between the two was a call by the captain within the last hour before the ship sank.